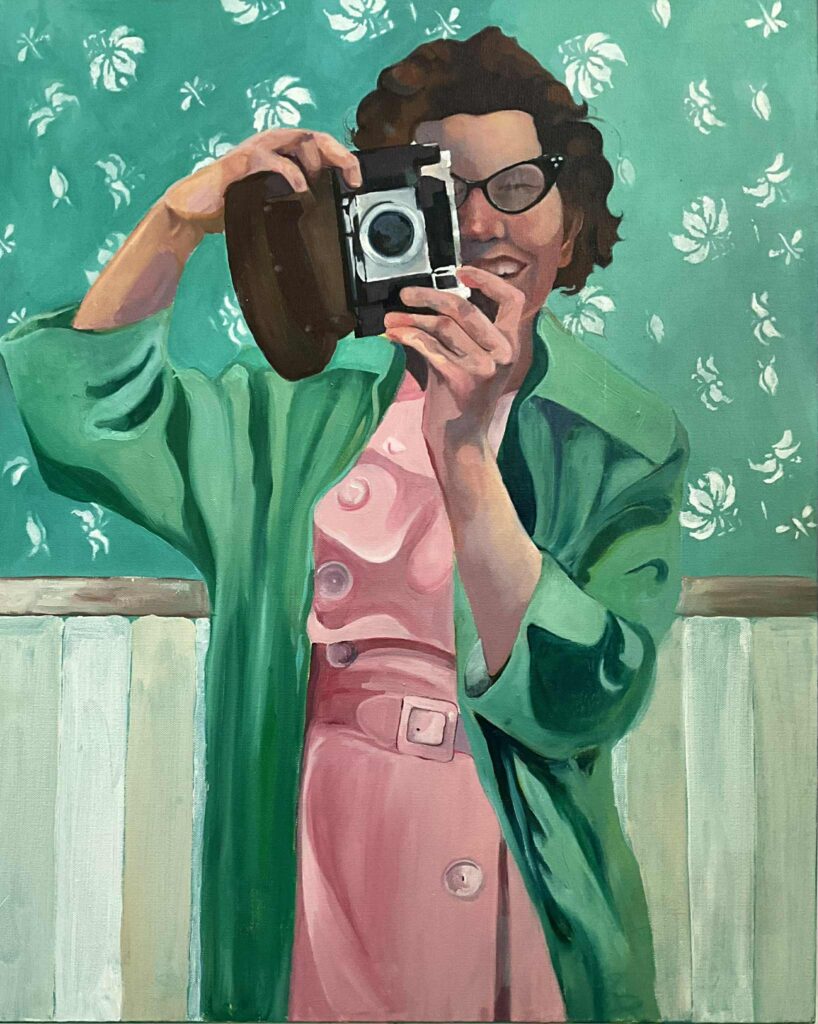

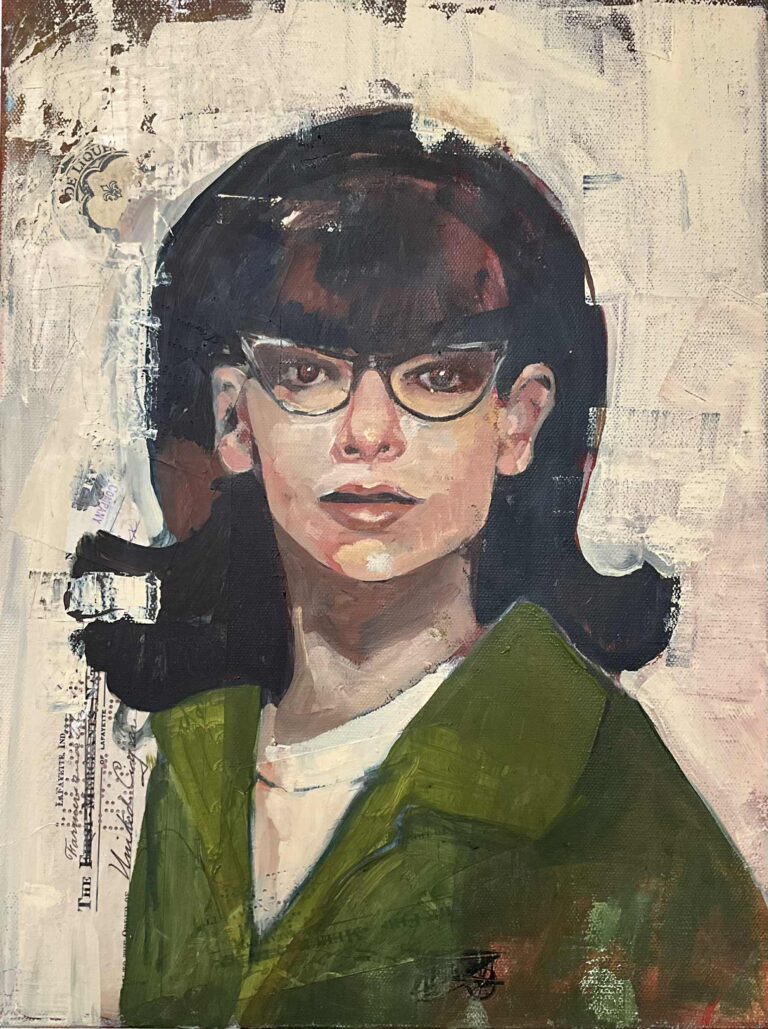

Return to the Kitchen: Bring ’Em Home… and Keep ’Em There

Wartime Womanpower, Peacetime Paternalism

During World War II, American women stepped up in ways the country had never seen. They built planes, worked as welders and machinists, and kept the economy running while American men were fighting overseas. To promote the effort, the U.S. government launched a coordinated messaging campaign through the Office of War Information (OWI), urging media outlets, companies, and artists to portray women as capable, patriotic workers. Factory work became a symbol of national strength and of women’s evolving place in society.

Double Duty: Gender, Labor, and the Fight for Equal Pay

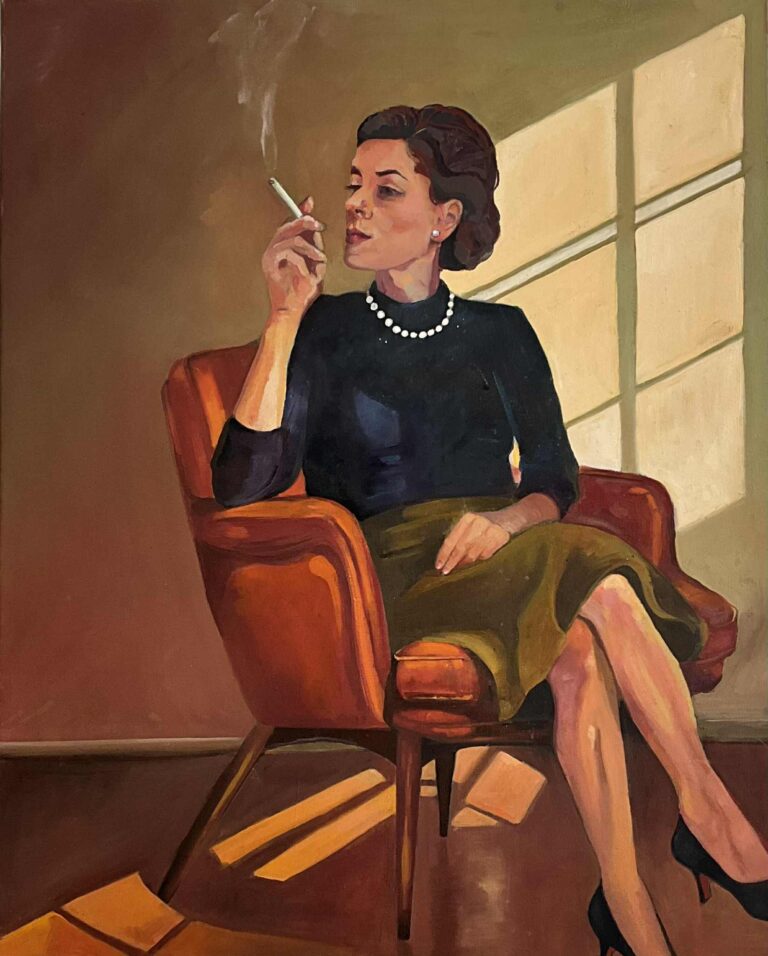

A Paycheck and a Pressure Cooker

Two landmark pieces of legislation in the early 1960s promised American women a long-overdue seat at the workplace table. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 required that men and women receive equal compensation for equal work. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, passed the following year, went even further, prohibiting employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. On paper, these were victories. They announced that women had every right to be in the boardroom, on the factory floor, and behind the desk, earning just as much pay as their male counterparts.

The Pill and the Kitchen Clock: How Birth Control Gave Women Power Over Time

A New Era in a Small Tablet

When the Food and Drug Administration approved Enovid in 1960, it gave American women access to more than a contraceptive. It offered them something society had long denied: control over time. That small, circular pill, taken each morning with breakfast or slipped discreetly into a purse, radically changed how women thought about their bodies, their schedules, and their futures. Suddenly, women could decide when to have children, or whether to have them at all, and to make plans that reached beyond the next menstrual cycle or maternity ward.

Sibling Rivalry: Intersectional Fault Lines in the Second-Wave Feminist Movement

Whose Liberation?

By the mid-1970s, second-wave feminism had become a household term and was making strides toward reshaping the national conversation around gender equality and the movement was steadily gaining momentum. Women were no longer afraid to demand equal pay, reproductive rights, and access to jobs and education previously denied them. Feminist leaders wrote bestsellers, testified before Congress, and filled the streets to call for equality. Behind the headlines, though, not everyone felt included. Women of color, working-class women, and queer activists often saw the mainstream women’s movement less as a universal fight for equality and more as an exclusive campaign for white, middle-class, heterosexual women.

Equal Rights, Divided Homes: The ERA and the Rise of Conservative Backlash

When Equality Knocks

The Equal Rights Amendment declared that equality of rights under the law “shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” It had been introduced and rejected in every session of Congress since 1923, but finally, amid the momentum of the women’s movement and with bipartisan support, it managed to pass in both houses in 1972 and was sent to the states for ratification.

Roe and the Architecture of Choice: Reproductive Rights in a Constitutional Frame

The Right to Choose

The decision to have a child in the US was rarely left to a woman before 1973. In most states, laws regulating abortion were not based on public health or constitutional principles, but on religious doctrine, paternalism, or outdated medical assumptions. Abortion was criminalized outright in thirty states, and thirteen others permitted it only under narrow exceptions, such as to save the mother’s life. In practice, this meant that most American women — regardless of education, income, or marital status — had no recognized legal authority over the most intimate decision of their lives: whether or not to bear a child.

Counterspace: Title IX and the Unmaking of the American Housewife

From Home Economics to Higher Ed

Before Title IX legislation, American girls were conditioned to build their dreams around home and family and to shape their ambitions to fit within its narrow frame. Home economics classes trained them to be considerate wives, efficient housekeepers, and attentive mothers. College, if it was in the cards at all, was often viewed as a steppingstone to marriage — a place for women to polish their manners, enhance their conversational skills, and become better companions to their future husbands. Women’s education, still rooted in the lingering ideals of Republican Motherhood, was justified as a means only to raise children to be informed citizens and assist them with their homework, not to pursue careers or personal ambitions of their own.

Institutionalizing Equality: The Birth of NOW and the Bureaucratization of the Feminist Movement

From Kitchen to Capitol

By the mid-1960s, the spark of second-wave feminism had already been lit in kitchens, classrooms, and coffee shops across America. Women were voicing their frustration with the limitations of domestic life, the persistent gender pay gap, and the unspoken expectation that they should give more and accept less — in their marriages, their jobs, and in the broader culture. But it wasn’t until 1966 that those frustrations took shape in a formal, institutional way with the founding of the National Organization for Women, or NOW.

Burning Dinner, Burning Bras: Everyday Radical Feminism

The Personal Was Political

By the late 1960s, a new generation of feminists had grown impatient with gradualism. They had read The Feminine Mystique, they had marched in civil rights protests, and they had sat through countless meetings of male-led leftist organizations where women took notes but only the men spoke. These radicalized feminists were dissatisfied with National Organization for Women’s measured approach and were unmoved by the tedious process of navigating the halls of power and mastering the language of bureaucracy. Radical feminists took their cause from their kitchen tables into the streets. Their tools weren’t policy memos or legal briefs, but a loud refusal to pretend that homemaking was some kind of dream job. And when they raised their voices and raised their fists, it was to demand more than equality in the workplace or access to credit cards in their own names. Radical feminists were questioning the very fabric of American womanhood, from marriage to motherhood, and specifically, the myth that their personal fulfillment existed only in their participation in those institutions.

Making Lunch, Making History: Black Women and the Foundations of Civil Rights

Revolution Simmering: The Kitchen as Command Center

In American history books, the civil rights movement is most often viewed through the lens of courtroom decisions, protest marches, and towering men’s speeches. But many of the era’s most sweeping public victories began far from podiums or picket lines in Black women’s kitchens. While these spaces were primarily reserved for household chores and meal preparation, they often doubled as meeting rooms for protest planning, building phone trees, and folding flyers, all against a backdrop of collard greens simmering on the stove and cornbread baking in the oven.